The transient’s key findings are:

- Layoffs harm all employees, however does the ache fluctuate by race?

- The evaluation makes use of administrative information to see how the long-run earnings of displaced employees fared throughout three completely different recessions.

- In the long term, Black and White displaced employees each have earnings roughly 30-40 % decrease than their same-race counterparts who weren’t laid off.

- Although the affect of layoffs is comparable, Black employees begin with decrease earnings, see slower earnings progress, and usually tend to lose a job within the first place.

Introduction

It’s effectively established that shedding a job hurts long-run earnings, however it’s unclear whether or not the affect varies by race. On the one hand, displaced Black employees could also be hindered relative to their White counterparts because of discrimination in hiring. Alternatively, displaced Black employees might have greater productiveness than laid-off White employees who in any other case seem related, as a result of employers discriminate in termination choices. Moreover, Black employees could also be much less prone to maintain “profession ladder” jobs, the place compensation features a premium for expertise, so job loss might affect them much less for that cause, too.

To find out the relative affect of job loss on Black and White employees, this transient, which relies on a current examine, focuses on the affect of displacement throughout three recessionary intervals: 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2008-09.1 The train makes use of administrative information from the U.S. Social Safety Administration (SSA) to match the earnings trajectories – 5 years earlier than and 10 years after every recession – of displaced employees relative to the trajectories of comparable employees who weren’t displaced.

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part opinions what is understood in regards to the affect of unemployment for Black and White employees. The second part introduces the information and methodology used for the evaluation. The third part presents the outcomes, which present that, by 10 years after the preliminary job loss, each Black and White displaced employees have earnings roughly 30-40 % decrease than same-race employees who weren’t displaced. The ultimate part concludes that whereas Black employees will not be disproportionately harmed by job loss in the long term, they start with decrease earnings, their earnings develop extra slowly than these of White employees, and they’re extra prone to lose their job in a recession within the first place.

Background

Black employees have all the time been more likely to be unemployed or underemployed than their White counterparts; they’re the primary to be laid off from struggling companies; and so they face longer spells of unemployment.2 But, whereas it’s well-known that job loss hurts the long-run earnings of displaced employees, current analysis doesn’t typically tackle how the impact may fluctuate by racial group.3

Theoretically, employees who lose their jobs because of macroeconomic or trade shocks might have hassle recouping misplaced earnings as a result of both their human capital depreciates whereas they’re unemployed or they lose an employer-employee relationship with unusually excessive productiveness.4 This lack of ability to totally get better is especially pronounced for employees who – because of their occupation – require important firm-specific data to be productive or maintain career-ladder jobs, which disproportionately reward lengthy tenure. As well as, a layoff is usually a detrimental sign of productiveness on the job market, carrying a wage penalty.

Black employees could also be differentially affected by layoffs in offsetting methods. First, Black employees who’re laid off may fare worse than equivalent White employees because of discrimination within the labor market.5 Since Black job-seekers sometimes obtain fewer callbacks than equally certified White folks, they will both search longer to realize the identical wage or finish the search earlier by accepting a decrease wage.6 Alternatively, Black employees, probably because of discrimination, are sometimes the primary to be laid off from struggling companies and should have greater productiveness than in any other case related laid-off White folks, which might allow them to get better misplaced earnings extra shortly when they’re rehired. Black employees are additionally much less prone to maintain career-ladder jobs, the place a layoff is most certainly to generate giant long-term earnings losses.7

Recognizing that every one these forces function concurrently, this evaluation goals at estimating the web affect on earnings from job lack of White and Black males. The comparability is proscribed to White and Black employees as a result of the race data is much less dependable for different ethnic teams; and it’s restricted to males as a result of, notably within the early recession, White ladies seem a lot much less hooked up to the labor power than Black ladies.8

Information and Methodology

The information come from SSA’s Steady Work Historical past Pattern (CWHS), which incorporates earnings information for a 1-percent pattern of the inhabitants. The benefit of this dataset is its measurement and reliability. The drawback is that it has very restricted demographic details about the employees.9

Figuring out Displaced Employees

Like prior research, this evaluation begins by figuring out a pattern of employees (ages 28-45) in three intervals of excessive unemployment: 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2008-09.10 The give attention to job loss throughout a recession is an try and determine employees whose termination was because of macroeconomic shocks, fairly than low productiveness.11 For every interval, the pattern is proscribed to employees with secure pre-recession jobs – that’s, employees who have been employed with the identical employer for 5 years previous to the recession. The earnings trajectories of these displaced are then in comparison with a management group who remained employed all through the recession.

After all, not all job separations are related to a loss in earnings; typically individuals who swap jobs see their earnings improve. Figuring out “displaced” employees entails discovering those that skilled a “substantial drop” in earnings. This calculation compares the separator’s common earnings within the 5 years earlier than the recession with common earnings through the recession years. Displaced employees are outlined as these whose share change in earnings falls beneath the twenty fifth percentile of this distribution.

Pattern Traits

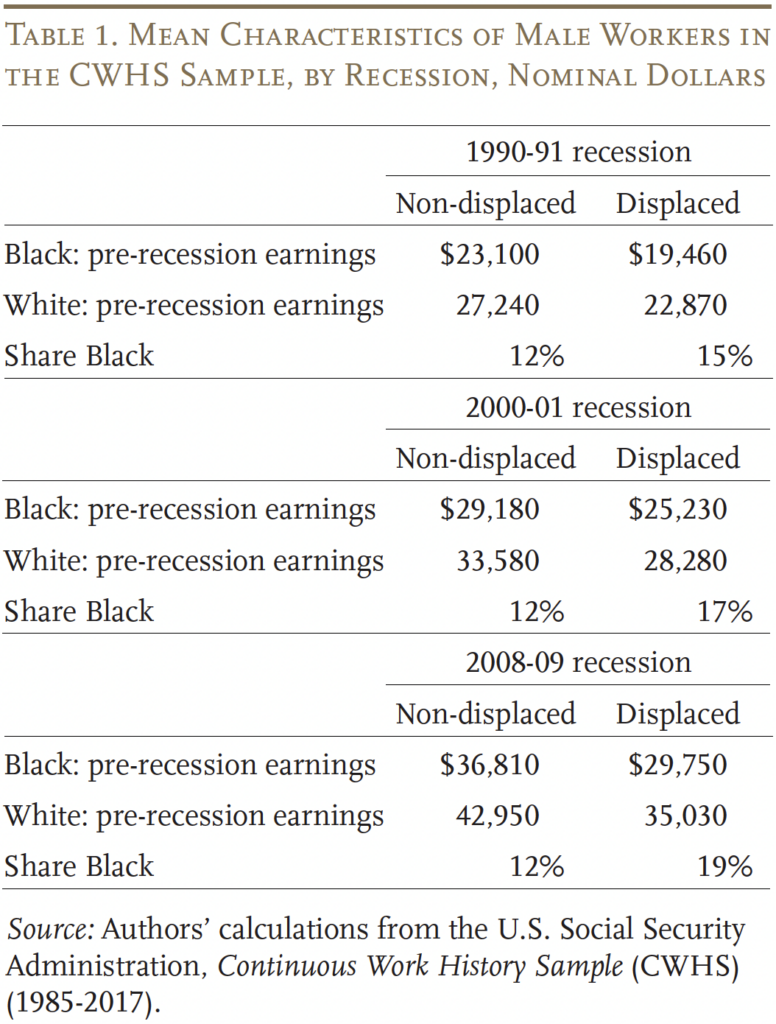

Earlier than describing the regression evaluation, it’s useful to think about the traits of displaced and non-displaced employees, by race (see Desk 1).12 A number of factors stand out. First, displaced employees have decrease pre-recession earnings than non-displaced employees of the identical race. Second, Black employees have decrease annual earnings than White employees, on common.13 Employees are round age 36 pre-recession (not proven in Desk 1). Notably, Black employees are considerably extra prone to be displaced throughout recessions, per prior literature.14

Having set the pattern, the evaluation is completed utilizing odd least squares regression.15 The dependent variable is log of earnings or an indicator of employment standing. Basically, the equation checks for differential pre-trends between displaced and non-displaced White employees 5 years previous to job loss after which estimates the impact of unemployment on their outcomes as much as 10 years post-layoff, whereas additionally estimating the differential impact of displacement for Black employees.

Outcomes

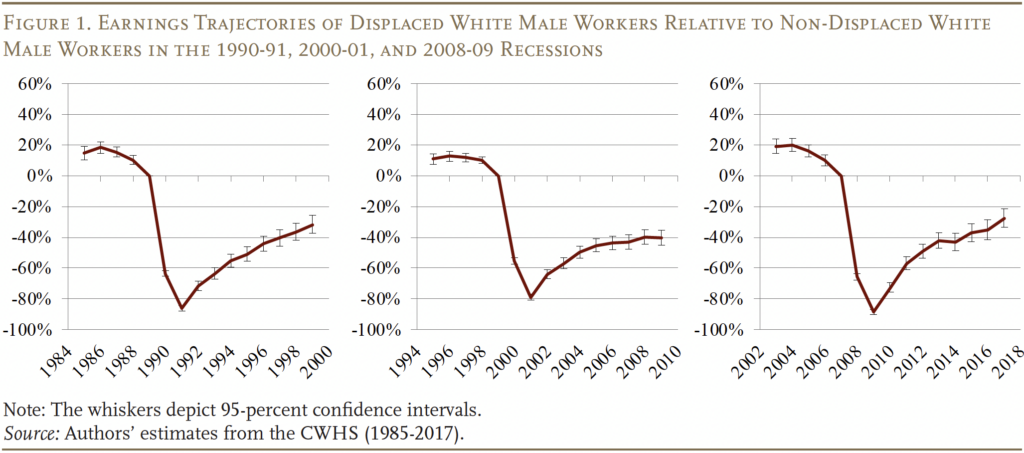

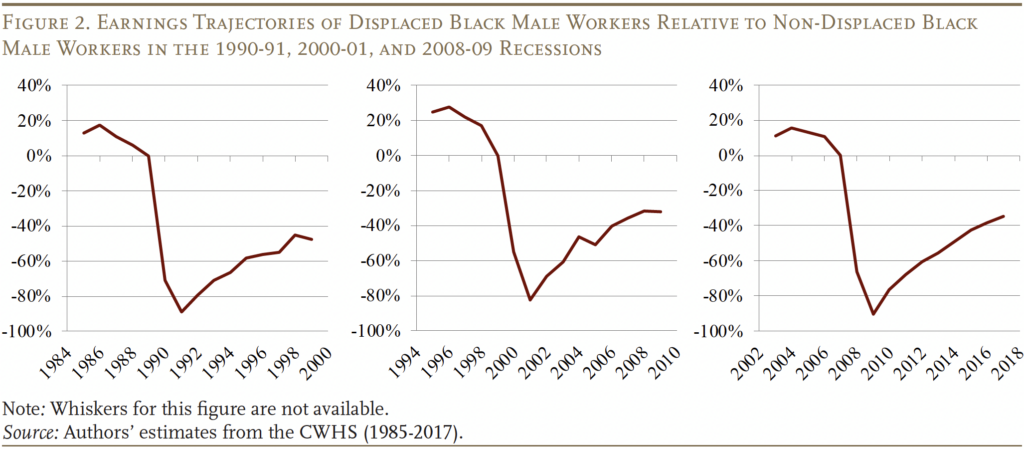

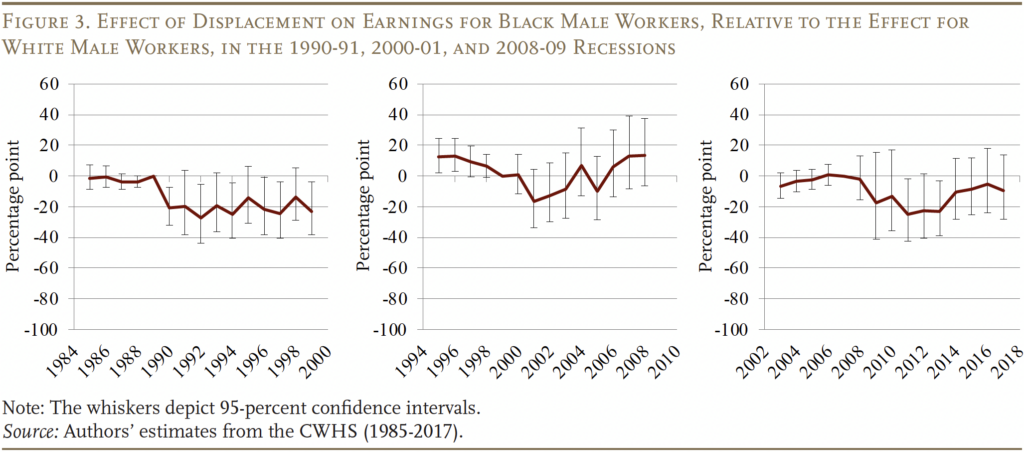

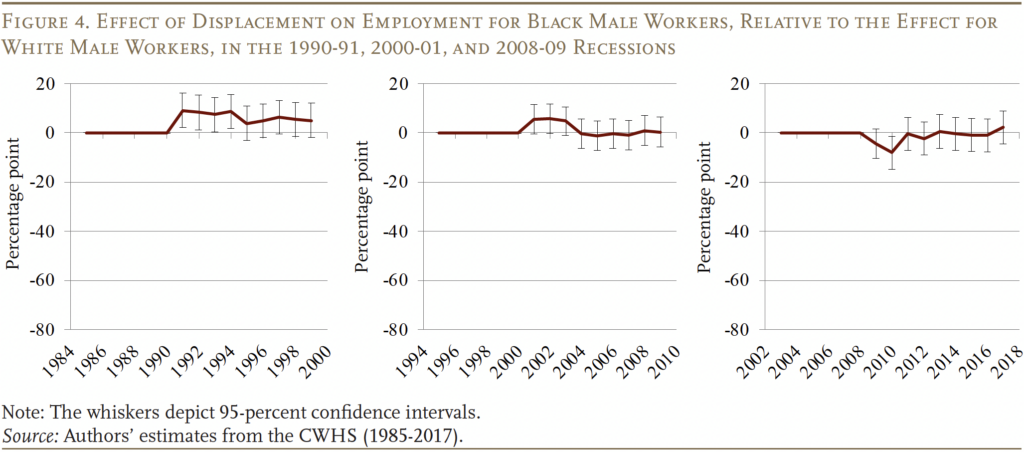

The regression outcomes for the impacts of job-loss on earnings and employment by race are proven graphically in Figures 1-4.16

Impact of Job Loss on Earnings of White Employees

Determine 1 exhibits the consequences of displacement on the earnings of re-employed White employees over the three recessions – that’s, it compares White displaced employees with White non-displaced employees.17 The distinction is proven in share phrases relative to the yr earlier than displacement. All three recessions present remarkably related patterns.18 First, White displaced employees constantly expertise a 55- to 66-percent drop in earnings within the yr of separation. Partially, this drop displays our definition of displacement as leaving a long-term employer and experiencing a change in earnings within the backside 25 % of separators within the yr of displacement. A extra significant measure of the loss is that earnings are likely to fall even additional for the displaced employees within the yr after separation, bottoming out at declines of 79 to 88 %. This later decline is not mechanical, however fairly displays an actual and devastating affect of separating from employment. Second, these earnings losses are long-lasting: White displaced employees by no means get better throughout the 10-year window after every recession. By the ultimate yr, White displaced employees nonetheless have earnings 28 to 40 % decrease than they’d have in any other case had.

Impact of Job Loss on Earnings of Black Employees

Determine 2 exhibits the earnings trajectories of Black displaced employees in comparison with Black non-displaced employees. Once more, all three recessions present related patterns. Very similar to White employees, Black displaced employees expertise an 80- to 90-percent drop in earnings within the yr following separation. On common, much like White displaced employees, Black employees by no means get better throughout the 10-year window after every recession. By the ultimate yr, Black displaced employees nonetheless have earnings 32 to 47 % decrease than they’d have in any other case had.

Differential Impact of Job Loss on Earnings of Black Employees

The important thing results of the evaluation is the comparability of how displacement impacts Black employees relative to White ones. Particularly, Determine 3 exhibits the affect of displacement for Black employees relative to their non-displaced Black counterparts, in comparison with the affect of displacement for White employees relative to their non-displaced White counterparts. The most important conclusion is that Black employees didn’t endure disproportionately from job loss in the long term. Sure, following the 1990-91 recession Black displaced employees skilled better losses than their White counterparts, however these estimates are very imprecise. And importantly, the next two recessions present a sample of restoration and no statistically significant distinction in outcomes by race.

Impact of Job Loss on Employment of Black and White Employees

One additional step is critical earlier than concluding that Black employees haven’t been harm greater than White employees from job loss, and that pertains to employment. The findings above are primarily based on the earnings expertise of displaced employees who discover a new job. If solely 10 % of Black folks discover new work, whereas 100% of White persons are reemployed, the findings wouldn’t be significant. Subsequently, Determine 4 exhibits the relative employment expertise of Black and White employees. Extra particularly, it exhibits the distinction in employment charges between displaced and non-displaced Black employees, in comparison with the distinction in employment charges between displaced and non-displaced White employees. Curiously, Black displaced employees really skilled optimistic – albeit modest – “extra employment” through the first few years of the 1990-91 recession, earlier than converging again to the identical stage as White displaced employees. The identical sample is discernible within the 2000-01 recession, though the distinction is barely marginally statistically important, and disappears by the Nice Recession. In different phrases, displaced Black employees do considerably higher by way of employment relative to non-displaced Black folks than their White counterparts. Thus, the conclusion of no distinction in earnings trajectories for Black and White employees is a significant discovering.

Conclusion

This examine considers whether or not the impact of displacement on earnings is worse for Black than for White employees, specializing in males who have been stably employed pre-displacement. The evaluation combines a sequence of pure experiments with administrative earnings information from the SSA. Particularly, it compares the earnings trajectories of Black and White employees who have been displaced throughout three recessionary intervals to employees of the identical race who weren’t displaced. The outcomes present that displaced male employees expertise giant and chronic declines in earnings and employment relative to the counterfactual, no matter race. Whereas Black employees are likely to lose extra in share phrases instantly following a job loss, this extra loss dissipates in the long term.

However, Black employees nonetheless face important labor-market headwinds as they begin off at decrease ranges of earnings and employment than their White friends and face a disproportionate danger of displacement. Furthermore, limiting the pattern to these with 5 years of secure employment (as is normal within the literature on displacement) might produce a pattern of Black employees who’re extra productive than the comparability pattern of White employees. Therefore, the findings might understate the extent of racial disparities in unemployment scarring. We depart this essential query for future analysis.

References

Altonji, Joseph G. and Charles R. Pierret. 2001. “Employer Studying and Statistical Discrimination.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(1): 313-350.

Braxton, J. Carter and Bledi Taska. 2023. “Technological Change and the Penalties of Job-Loss.” American Financial Assessment 113(2): 279-316.

Cajner, Tomaz, Andrew Figura, Brendan M. Worth, David Ratner, and Alison Weingarden. 2020. “Reconciling Unemployment Claims with Job Losses within the First Months of the COVID-19 Disaster.” Washington, DC: U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Cooper, Daniel. 2013. “The Impact of Unemployment Length on Future Earnings and Different Outcomes.” Working Paper 13-8. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Financial institution of Boston.

Sofa, Kenneth A. and Robert Fairlie. 2010. “Final Employed, First Fired? Black-White Unemployment and the Enterprise Cycle.” Demography 47(1): 227-247.

Davis, Steven J. and Until von Wachter. 2011. “Recessions and the Prices of Job Loss.” Brookings Papers on Financial Exercise 1-72.

Diette, Timothy M., Arthur H. Goldsmith, Darrick Hamilton, and William Darity Jr. 2018. “Race, Unemployment, and Psychological Well being within the USA: What Can We Infer Concerning the Psychological Price of the Nice Recession Throughout Racial Teams?” Journal of Economics, Race, and Coverage 1: 75-91.

Dwyer, Debra Sabatini and Olivia S. Mitchell. 1998. “Well being Issues as Determinants of Retirement: Are Self-Rated Measures Endogenous?” Journal of Well being Economics 18: 173-193.

Elvira, Marta M. and Christopher D. Zatzick. 2002. “Who’s Displaced First? The Position of Race in Layoff Choices.” Industrial Relations 41(2): 329-361.

Farber, Henry S. 2003. “Job Loss in the US.” Working Paper 9707. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Farber, Henry S., John Haltiwanger, and Katherine G. Abraham. 1997. “The Altering Face of Job Loss in the US, 1981-1995.” Brookings Papers on Financial Exercise. Microeconomics. 1997: 55-142.

Forsythe, Eliza and Jhih-Chian Wu. 2021. “Explaining Demographic Heterogeneity in Cyclical Unemployment.” Labour Economics 69: 1-15.

Guvenen, Fatih, Fatih Karahan, Serdar Ozkan, and Jae Music. 2017. “Heterogeneous Scarring Results of Full-12 months Non-Employment.” American Financial Assessment: Papers and Proceedings 107(5): 369-373.

Jacobson, Louis S., Robert J. LaLonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan. 1993. “Earnings Losses of Displaced Employees.” American Financial Assessment 83(4): 685-709.

Kijakazi, Kilolo, Karen E. Smith, and Charmaine Runes. 2019. “African American Financial Safety and the Position of Social Safety.” Transient. Washington, DC: City Institute.

Lachowska, Marta, Alexandre Mas, and Stephen A. Woodbury. 2020. “Sources of Displaced Employees’ Lengthy-Time period Earnings Losses.” American Financial Assessment 110(10): 3231-3266.

Nekoei, Arash and Andrea Weber. 2017. “Does Extending Unemployment Advantages Enhance Job High quality?” American Financial Assessment 107(2): 527-561.

Neumark, David. 2018. “Experimental Analysis on Labor Market Discrimination.” Journal of Financial Literature 56(3): 799-866.

Quinby, Laura D. and Gal Wettstein. 2025. “Is the Scarring from Unemployment Worse for Black Employees?” Working Paper 2025-8. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston Faculty.

_________. 2023. “Are Older Employees Able to Working Longer?” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance.

Rose, Evan Okay. and Yotam Shem-Tov. 2023. “How Replaceable Is a Low-Wage Job?” Working Paper 31447. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Ruhm, Christopher J. 1991. “Are Employees Completely Scarred by Job Displacements?” American Financial Assessment 81(1): 319-324.

Schmieder, Johannes F., Until von Wachter, and Stefan Bender. 2016. “The Impact of Unemployment Advantages and Nonemployment Length on Wages.” American Financial Assessment 106(3): 739-777.

Stevens, Ann Huff. 1997. “Persistent Results of Job Displacement: The Significance of A number of Job Losses.” Journal of Labor Economics 15(1): 165-188.

Sullivan, Dan and Until von Wachter. 2009. “Job Displacement and Mortality: An Evaluation Utilizing Administrative Information.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(3): 1265-1306.

Thomson, Owen. 2021. “Human Capital and Black-White Earnings Gaps, 1966-2017.” Working Paper 28586. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. “Labor Power Traits by Race and Ethnicity, 2019.” Washington, DC.

U.S. Social Safety Administration. Steady Work Historical past Pattern, 1985-2017. Washington, DC.

von Wachter, Until M., Elizabeth Weber Handwerker, and Andrew Okay. G. Hildreth. 2009. “Estimating the ‘True’ Price of Job Loss: Proof Utilizing Matched Information from California 1991-2000.” Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Heart for Financial Research.

von Wachter, Until, Jae Music, and Joyce Manchester. 2009. “Lengthy-Time period Earnings Losses Resulting from Mass Layoffs Through the 1982 Recession: An Evaluation utilizing U.S. Administrative Information from 1974 to 2004.” Introduced on the IZA/CEPR eleventh European Summer season Symposium in Labour Economics. Buch/Ammersee, Germany.